Transforming Collections

Posted: February 17, 2012 | Author: Steven Harris | Filed under: Collection Philosophy, Professional development | Tags: ALCTS, training | Leave a comment »ALCTS E-Forum:

Date: February 22 & 23

Description: “Join us to talk about all the ways our collections are changing and discuss topics such as handling new formats, preservation methods, repository services, planning for the future, best practices for moving forward, and budgeting for changing times. Come share your success stories about how you are meeting the research, teaching, and recreational needs of your users of today and tomorrow.”

Occupy Elsevier

Posted: February 2, 2012 | Author: Steven Harris | Filed under: Collection Philosophy, Professional development | 1 Comment »There is an academic boycott of Elsevier going on now that is getting a lot of press and social media chatter. (See “The Cost of Knowledge.”) I know Rick Anderson has written a post about the boycott over at Scholarly Kitchen, but I am going to refrain from reading his thoughts until I get this post down. (Perhaps a follow-up after I read it.) In the interest of disclosure, I should say that I work in a library that is a big customer of Elsevier. In fact, we recently licensed the “Freedom Collection” of bundled journals from that publisher.

The point of the boycott is to encourage scientists and scholars to sign a pledge not to publish in, referee for, or do editorial work with any Elsevier journals. The rationale given on the web page is three-fold (my paraphrase): 1) their prices are high, 2) their practice of bundling journals saddles libraries with a lot of titles they don’t want, 3) they support SOPA, PIPA, and the Research Works Act.

I do not deny that each of these points is bad for libraries and for scholarly communication generally, nor that they apply to Elsevier. But I do want to raise a couple of points of concern about the boycott.

- The boycott seems a bit like déjà vu all over again. Our discourse regarding scholarly communication has been vilifying Elsevier specifically for at least 20 years. I often have conversations with faculty in which they say, “I know Elsevier is bad, but…” or “I thought we were supposed to avoid Elsevier…” And, yet, with that knowledge, faculty continue to publish in Elsevier journals and serve on Elsevier editorial boards. In short, all that negative publicity has done little to affect the bottom line of Elsevier, but more importantly, has not changed the high rating and impact of many Elsevier journals.

- All three of the issues raised by the boycott apply equally to dozens of other scholarly publishers. Why are they not included in the boycott? What can the boycott hope to achieve if other publishers simple take up what Elsevier loses? Are we to believe that an open access paradise will be achieved by taking on the large scholarly publishers one at a time? We will have a sequence of boycotts for Wiley, Springer, Sage, Taylor & Francis?

- I have always thought that libraries were always stuck between a rock and a hard place regarding high-priced scholarly journals. The solution has never been that libraries should simply cancel their subscriptions. The very process of promotion and tenure in higher education requires that faculty publish in the highest rated journals, regardless of the sales practices of those journals. I don’t think, however, that the boycott as it is currently organized presents a coordinated effort that will get the desired results.

I admit to be at a loss to how this boycott ought to be organized. The rot here goes to the very heart of the P&T system in higher eduction. Individual scientists can sign the boycott, but that will have little impact if, at the point of tenure review, entire academic departments (or even entire universities) do not discount the value high-price journals and take predatory publishing into account. It is difficult to see how that kind of journal evaluation can take hold without coordination that goes even beyond department and university, encompassing entire academic disciplines and all the journals serving those disciplines.

Don’t Feed the Trolls

Posted: November 7, 2011 | Author: Steven Harris | Filed under: Collection Philosophy, Professional development | Leave a comment »The library world has two kinds of trolls stalking it lately. Unfortunately, these trolls often have access to major editorial pages from which to pour vitriol down upon us.

Troll #1: We don’t need libraries anymore! These trolls are addicted to those dangerous “everything is on the Internet” hallucinogens. Public libraries are most often in the sights of these kinds of trolls, but other kinds of libraries also come under attack. Newspaper editorial pages are full of their opinion pieces about how no one uses libraries anymore. “We don’t need help finding things anymore. We have Google and Bing.” Or, “We can just buy whatever we want for our Kindle. Information is cheap!” Forget that everything is not free and available to Google’s eyes or Kindle download. Forget that a lot of the information libraries provide is expensive, highly vetted, and still used extensively by library customers. Forget that the service of training users to effectively discover and use information is highly valued in all of our communities. These trolls won’t listen to those arguments.

Troll #2: Don’t you dare change my library of 40 years ago! These trolls are stuck in a time warp. They have fond memories of 1974, when they completed their Ph.D and bought a Chevy Vega. Academic libraries that try innovative new approaches to information delivery will likely raise the ire of these trolls. They will make smug comments about learning commons, remote storage, and any kind of technology that involves electrons in their editorial diatribes. “Any fool knows you need to look at the print journal volumes to do real research.” Which would surprise the other library users who download to the tune of [over] a million journal articles a year, while the bound volumes sit quietly – peacefully in the basement, rarely reshelved, infrequently discovered sitting next to the photocopier. They proudly give research assignments to undergraduates with the instructions NO ELECTRONIC RESOURCES WILL BE ACCEPTABLE. “It is imperative that students know how to use Poole’s Index to Periodicals if they hope to understand the research process.” Forget that some of your electronic resources include Poole’s (and a lot more) anyway. Forget that academic publishers are plunging headlong into a new digital world. Forget that scholarship itself is embracing and exploring new ways of sharing discoveries, many of which never grace the pages of a print journal. They know what is best and what is best never changes.

My advice is not to feed the trolls. Despite the prominence of their editorial invective, they are the minority. We don’t need to counter their arguments when 90% of the community disagrees with them anyway. Let your gate-counts, check-outs, and downloads do their own talking. If anyone who matters asks, have those data at hand. Talk about your programs that are well attended. Show your letters of thanks and survey responses that tell a different story than what the trolls spin. Know in your heart that you are serving the needs of the community and talk about that with enthusiasm to those who want to listen. But don’t feed the trolls. It’s not worth it.

New Wine in New Bottles

Posted: October 22, 2011 | Author: Steven Harris | Filed under: Collection Philosophy | Leave a comment » (OK! I’m on again about renting versus owning!) I was engaged in a recent discussion on Google+ about the idea of micro-payments for information based on circulation. It was the basis of a presentation at Internet Library, which I did not attend. (Apparently, the e-book sessions at IL were huge this year.) Anyway, I’m surprise at how tenaciously we librarians cling to the idea of owning information–sometimes coming from the same people who say information wants to be free. I once felt that way. “Not another thing that requires a subscription!”

(OK! I’m on again about renting versus owning!) I was engaged in a recent discussion on Google+ about the idea of micro-payments for information based on circulation. It was the basis of a presentation at Internet Library, which I did not attend. (Apparently, the e-book sessions at IL were huge this year.) Anyway, I’m surprise at how tenaciously we librarians cling to the idea of owning information–sometimes coming from the same people who say information wants to be free. I once felt that way. “Not another thing that requires a subscription!”

Now, however, I will cling as tenaciously to the idea that all of our library collection ownership models were developed to handle discrete, physical containers of information. Digital information doesn’t fit the model. It warrants new approaches. I think we should be working our tails off developing new models and presenting those to vendors and publishers. Because, you know, they are going to invent their own systems, if left to their own devices.

We need a sandbox, a laboratory, as it were, for developing new information ownership/access models. Some place to test them out in a safe way. And we need people in our ranks who understand economic and ecological modelling to work on these ideas.

photo courtesy of Claire Schmitt

Berlin Declaration

Posted: October 17, 2011 | Author: Steven Harris | Filed under: Collection Philosophy, Professional development | Tags: open access, scholarly communication | Leave a comment » The Berlin Declaration on open access was written in 2003 under the direction of the Max Planck Society in Germany. Many organizations in Europe, Asia, and Latin America have signed the declaration, but North American organizations have been rather thin on the list of signatories. The main thrust of the statement is that open access is good for scholars and that they should strive to resolve that problems that arise when open access and traditional academic promotion and tenure come together.

The Berlin Declaration on open access was written in 2003 under the direction of the Max Planck Society in Germany. Many organizations in Europe, Asia, and Latin America have signed the declaration, but North American organizations have been rather thin on the list of signatories. The main thrust of the statement is that open access is good for scholars and that they should strive to resolve that problems that arise when open access and traditional academic promotion and tenure come together.

With the Berlin 9 Open Access Conference scheduled to occur in Washington D.C. in November, 2011, many North American universities and academic organizations have been hoping to show greater American participation. My university got on board. As the out-going chair of the Faculty Senate Library Committee, I was asked to draft a resolution about the Berlin Declaration. I wrote something up and presented it to the Faculty Senate. They accepted it and passed it on for our Provost to sign, which he has promised to do.

I thought the text of my resolution might be useful for others who would like their university to endorse the Declaration. I’ve attached a generic version of what I wrote. The specific names and titles have been replaced. Feel free to use any portion of this resolution that you like. No acknowledgment required.

Collection Communication

Posted: July 5, 2011 | Author: Steven Harris | Filed under: Collection Philosophy | Tags: communication, information overload | 1 Comment »I’ve been thinking about an issue for library collections recently. I might like to do a research project on this topic but have not pushed through the inertia to get working on it. The topic is: communication about collections. There are so many issues about library collections that require communication with a wide variety of constituents both within the library staff and in the user community. The number of issues that require communication is almost never ending. And the variety of constituents is daunting.

I started keeping a spreadsheet of all the different communication issues we have:

- Product trials

- New products

- Vendors visits

- Vendor training announcements

- New approval titles

- Renewal notices

- New product requests

- Order problems

- Fund problems

- Orders or requests (from librarians or users)

- Invoice (received or to be paid)

- Claims

- Connectivity problems

- Service Outages

Some of those are entirely internal. Some are issues that we communicate outward to library staff and users. Some are issues that users communicate to us. ERMs were designed to handle some of the internal communication issues (although even at those, they don’t do a very good job), but ERMs were never intended to be the means of pushing out the entire gamut of communication elements to a library community.

What can we use to meet all these communication needs? I’ve been pondering that for my own library and not come up with a good solution. Probably no one tool is right for everything. But we do have a lot more options now days. We use a lot of email discussion lists in my library, but, personally, I’d rather eat a bag of glass than be added to another listserv.

So, the number of communication tools is equally daunting:

- Telephone

- Text message

- Chat

- Personal email

- Group email list

- Newsletter (print or electronic)

- Face to face

- Webpage

- Intranet

- Local network drive

- Wiki

- Calendar

- Blog

- Libguides

- Course management system

- Skype

- RSS

- Adobe Connect

- YouTube

- Other Social Media

And probably 500 other things. Ideally, it would be nice if we could integrate all of this into a single system. A blog platform like WordPress might begin to do the job, but I haven’t figure out how to sort out the internal and the public. So many puzzles to solve.

What is your library using for internal and external communications about library collections issues? Help me out here!

image credits:

Very Large Array: Rick Ortiz (Flickr)

telephone: Frédéric BISSON (Flickr)

Mobeus Trip

Posted: June 16, 2011 | Author: Steven Harris | Filed under: Collection Philosophy, Online collections | Leave a comment » The other day, I was at a retreat for my library’s administrative team. We were doing some strategic visioning. I managed to get some of my ideas about collections embraced. Well, actually, they were all pretty prepared to accept a lot of what I want to have as part of our collection vision. In fact, our head of discovery services (cataloging) was pretty quick to recognize the key concept: discovery and collections are one and the same. We spent some time coming up with metaphors for that idea. It’s the yin/yang of the library. Or maybe its a mobeus strip. Collections and discovery on different sides of the strip…wait a minute!

The other day, I was at a retreat for my library’s administrative team. We were doing some strategic visioning. I managed to get some of my ideas about collections embraced. Well, actually, they were all pretty prepared to accept a lot of what I want to have as part of our collection vision. In fact, our head of discovery services (cataloging) was pretty quick to recognize the key concept: discovery and collections are one and the same. We spent some time coming up with metaphors for that idea. It’s the yin/yang of the library. Or maybe its a mobeus strip. Collections and discovery on different sides of the strip…wait a minute!

There are a couple of other key concepts to this vision. Discovery is seamless, which is to say all discovery looks the same. There are no separate interfaces. It’s all one interface, one discovery platform (though perhaps with many customization and personalization features). The other concept, however, is that the collection is a hybrid. Some of it is an owned physical collection, some of it is subscription-based, some free, some curated local data, much of it is digital. A lot of it is not owned or subscribed to in any normal sense of those words, but access to it is mediated instantaneously or on-the-fly. Demand driven collections that happen at the point of need.

There are a couple of other key concepts to this vision. Discovery is seamless, which is to say all discovery looks the same. There are no separate interfaces. It’s all one interface, one discovery platform (though perhaps with many customization and personalization features). The other concept, however, is that the collection is a hybrid. Some of it is an owned physical collection, some of it is subscription-based, some free, some curated local data, much of it is digital. A lot of it is not owned or subscribed to in any normal sense of those words, but access to it is mediated instantaneously or on-the-fly. Demand driven collections that happen at the point of need.

The discovery mechanism is what allows your library users to have access to information. In this environment, library staff will be engaged in pointing the discovery mechanism in the direction of collections or repositories that are useful. Although I think users should also be able to point it anywhere they like. More to the point, library staff will be engaged as well in creating metadata for information objects that will make them more discoverable, regardless of whether they are already owned or subscribed to. I guess this also means that cataloging and acquisitions are more or less the same process.

Preserve and Protect

Posted: May 11, 2011 | Author: Steven Harris | Filed under: Collection Philosophy | Tags: collaborative collection management, weeding | 2 Comments » Weeding! It’s a swear word for a lot of academic librarians. Our public library counterparts are more amenable to the whole thing. (See Awful Library Books.) Academic librarians, however, take very seriously the charge to preserve the scholarly record. In an online discussion recently with my literature librarian colleagues, many of them said they would NEVER weed a literature book. I think that begins to be an untenable position. Space in academic libraries rarely grows at the rate that the collection grows. Given that situation, you can choose to either to stop growing the collection or begin to dispose of items that are not vital for your local population. The response to that is typically: “well, I thought about getting rid of a book once, and lo and behold, 10 years later I really needed that book.” Most anti-weedenists are willing to push that number years to infinity. What if someone needs it 20 years, 50 years, 300 years from now? It’s not sustainable, my friend.

Weeding! It’s a swear word for a lot of academic librarians. Our public library counterparts are more amenable to the whole thing. (See Awful Library Books.) Academic librarians, however, take very seriously the charge to preserve the scholarly record. In an online discussion recently with my literature librarian colleagues, many of them said they would NEVER weed a literature book. I think that begins to be an untenable position. Space in academic libraries rarely grows at the rate that the collection grows. Given that situation, you can choose to either to stop growing the collection or begin to dispose of items that are not vital for your local population. The response to that is typically: “well, I thought about getting rid of a book once, and lo and behold, 10 years later I really needed that book.” Most anti-weedenists are willing to push that number years to infinity. What if someone needs it 20 years, 50 years, 300 years from now? It’s not sustainable, my friend.

Here is what IS sustainable: a coordinated approach to preserving the scholarly record. Librarians need to think and work in a collective way, across multiple collections. Each library focuses its efforts on preserving a section of the scholarly record. The rest of the collection is gravy, as it were. It can be maintained as long as it is serving the local needs. When it is no longer serving that need, it becomes expendable. But not to worry. Some other library considers that material to be part of its preservation responsibility. So, the University of New Mexico, for example, is pledged to preserve materials about New Mexico, the American Southwest, Hispanic and Chicano culture, Latin American studies, and Pueblo culture. Of course, we also preserve anything published by our university press and by authors associated with our university or our state.

We would also keep a core of materials that serves any our of curriculum needs. Undergraduates would have the assurance that they can study any subject that interests them…to an undergraduate level of depth. A research level collection we would let be driven by whatever the current needs are, but we would not feel compelled to keep that material beyond the period of its current need, unless it was in one of our areas of pledged preservation interest.

There are now many tools that make this kind of distributed preservation work possible. JSTOR was intended, from the beginning, to be a way that librarians could have peace of mind about disposing of particular journal volumes that were available in a safe online archive. Most libraries never took JSTOR up on the offer to get rid of those journals that are in the archive. But there are other resources that begin to provide additional layers of preservation. LOCKSS, CLOCKSS, and Portico all offer additional preservation of digital content. Google Books provides digital copies of many public domain books. Many of those digital copies are further preserved by the Hathi Trust.

Several consortia are also developing a means of preserving print materials in a distributed way. WEST, the Western Regional Storage Trust, is developing plans for libraries to cooperate in creating a distributed repository of print journals. Most of their initial target materials will be items that have significant digital preservation and duplication as well.This list goes on and on of library consortia and organizations that are preserving print elements of the scholarly record: California Digital Library, Greater Western Library Alliance, Center for Research Libraries.

All of these factors can work to make a distributed preservation plan work:

- mass digitization (Google, Internet Archive, Hathi)

- cooperative, distributed print respositories (WEST, CDL, GWLA, etc.)

- cooperative digital preservation initiatives (LOCKSS, CLOCKS, Portico, Hathi)

More initiatives like these will flourish in coming years. At a certain point, we need to say, these materials are widely available digitally, a print copy is safely housed in a library repository, and the level of use locally suggests that I don’t need a copy sitting on my shelves any longer. Time to make room for something else.

Photo courtesy of tobym on Flickr: http://www.flickr.com/photos/48089670@N00/179449318/

Unused Portion

Posted: May 1, 2011 | Author: Steven Harris | Filed under: Collection Philosophy | 3 Comments » Math Math Math. I keep thinking about math. I blame Eric Hellman.

Math Math Math. I keep thinking about math. I blame Eric Hellman.

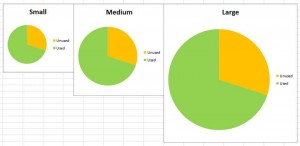

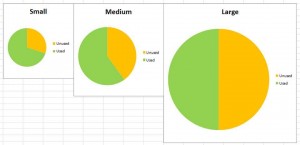

One of the elements about patron-driven collections that I talk about a lot at my institution is that it doesn’t seem like a good use of funds to buy a lot of books that never circulate. (See Hardesty or Kent.) A thought that keeps coming to mind is that it is probably impossible for anyone to predict exactly what is going to get used by another person (librarians predicting for students or faculty, faculty predicting for other faculty, vendors predicting for everyone). Thus, there will always be a percentage of a “selected” collection that never circulates. Is that percentage static? In other words, will 30% of the collection go unused regardless of whether the collection has 200,000 volumes or 20 million volumes.

In most previous library collection development models, even if the unused portion remains a constant, it makes sense to increase the size of the library as much as possible. A bigger collection will mean more used items (and more unused items too). A few questions about this model come to mind. Is the unused portion really constant? Might a smaller collection actually circulate at a higher rate? And is it really worth the additional expense of growing the collection as much as possible? Is there a point of diminishing returns?

I think a mix of patron-driven and selected collections might be the most effective. Librarians and approval plans could supply a core of materials. Although, as I’ve suggested, a percentage of those would likely never be used. But it would be a smaller amount of selection than in the past. Users then would otherwise get what they want in an on-demand fashion. This kind of model does suggest that we need to deliver user-requested materials as quickly as possible. Students, for example, may not want to wait 2 weeks, even 2 days for materials to be available. Ebooks, of course, are ideally suited for this kind of process. Many ebook vendors are now offering on-demand collection building models. Can we afford to continue building the just-in-case kinds of collections? Or should we be embracing the patron-driven, just-in-time kind of plan?

I think a mix of patron-driven and selected collections might be the most effective. Librarians and approval plans could supply a core of materials. Although, as I’ve suggested, a percentage of those would likely never be used. But it would be a smaller amount of selection than in the past. Users then would otherwise get what they want in an on-demand fashion. This kind of model does suggest that we need to deliver user-requested materials as quickly as possible. Students, for example, may not want to wait 2 weeks, even 2 days for materials to be available. Ebooks, of course, are ideally suited for this kind of process. Many ebook vendors are now offering on-demand collection building models. Can we afford to continue building the just-in-case kinds of collections? Or should we be embracing the patron-driven, just-in-time kind of plan?

References:

Hardesty, L. 1981. “Use of library materials at a small liberal arts college.” Library Research 3: 261–-82.

Kent, A., et al. 1979. Use of library materials: The Universityof Pittsburgh study. New York: Marcel Dekker.